Follow Scott

Recent Tweets

- Waiting for Twitter... Once Twitter is ready they will display my Tweets again.

Latest Photos

Search

Tags

anniversary Balticon birthdays Bryan Voltaggio Capclave comics Cons context-free comic book panel conventions DC Comics dreams Eating the Fantastic food garden horror Irene Vartanoff Len Wein Man v. Food Marie Severin Marvel Comics My Father my writing Nebula Awards Next restaurant obituaries old magazines Paris Review Readercon rejection slips San Diego Comic-Con Scarecrow science fiction Science Fiction Age Sharon Moody Stan Lee Stoker Awards StokerCon Superman ukulele Video Why Not Say What Happened Worldcon World Fantasy Convention World Horror Convention zombies

©2025 Scott Edelman

I appeared on the panel “The Moral Distance Between the Author and the Work” at the 2010 World Fantasy Convention in Columbus, along with Eric Flint, Nancy Kress, Paul Witcover, Kathryn Cramer, and Jack Skillingstead. The room was packed, with several hundred people present, and the discussion grew so lively near the end that we almost failed to yield the room.

Here’s how the panel, which is embedded in four parts below, was described in the Pocket Program:

What do we make of good art by bad people, or at least people of whom we disapprove? Richard Wagner was a particularly vile anti-Semite, but he still wrote “Kill Da Wabbit!” and other great music. Should we listen? The official Nazi film industry made one very good fantasy film (BARON MUNCHAUSEN, to which the Terry Gilliam version owes a good deal). Should we watch this? What about an author who is a convicted child molester? Should we read his novel? CAN we read it for itself? Is it possible to truly experience any form of art as a thing until itself, rather than the product of its creator?

If the three readings I’ve shared so far from World Fantasy, designed to make you wish you’d made it to Columbus, weren’t enough for you, here are two more.

First up, Kij Johnson, reading two short shorts.

In Which I Make You Feel Even MORE Miserable For Missing the World Fantasy Convention

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

K. Tempest Bradford, Kathe Koja, Mary Robinette Kowal, World Fantasy Convention

Posted date:

October 30, 2010 |

No comment

As I indicated yesterday, I won’t fully enjoy the World Fantasy Convention here in Columbus unless I know you’re watching from afar and are kicking yourself for not being here. To make sure you’re doing just that, here are two additional readings I attended Friday.

First up, K. Tempest Bradford, who is accompanied in the reading of her short story by Mary Robinette Kowal.

Next, Kathe Koja, reading from her new novel Under the Poppy. (more…)

You all remember Edelman’s First Rule of Convention-Going, also known as Edelman’s Schadenfreude Rule of Convention Reporting, don’t you?

It states that all convention reporting must occur while a convention is still ongoing, because it’s insufficient for me to be having a wonderful time. YOU must KNOW I’m having a wonderful time and be miserable because you’re not there also having a wonderful time, and kicking yourself, thinking, “If I jumped in my car, hopped on a plane RIGHT NOW, I could be having a wonderful time, too!”

Which is why I’m sharing the following video taken a scant 12 hours ago here in Columbus, Ohio at the World Fantasy Convention. Alaya Dawn Johnson read from a work in progress, and you could have been there.

Nyah, nyah, nyah!

What I Must Really Think of My Friends (and Killer Kowalski)

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

dreams

Posted date:

October 22, 2010 |

No comment

I woke to a dream this morning that was far too interesting to fit into 140 characters as were all the other dreams I’ve been tweeting these many months, and so I waited until now to tell it to you.

I was in a small hotel ballroom, occupied by no more than 50 people. Into the room, one at a time, came modern day professional wrestlers, and the crowd made much of them, cheering, taking pictures, getting autographs. But then came Killer Kowalski, an old-school wrestler, and he was ignored. (In real life, of course, when alive, he would have ben as mobbed as anyone.)

I thought this was a shame, so I went over to him, and starting telling him about my grandfather the bookie (yes, he was one) and held out my camera for someone to take a picture of the two of us.

Suddenly, there was Friend A, who will go unnamed for reasons which will soon become clear. I asked him to snap a picture, and he tried and failed repeatedly. The first shot had microphones blocking our faces, the next, stanchions. Then, we were out of focus. Again and again he tried, but whatever he did, he failed. He was too inept to successfully take a picture of me and Killer.

So I took the camera away and handed it to Friend B, who also appeared as if by magic. I put my arm around Killer’s shoulders; he did the same to me. And this second friend holding the camera turned thoughtful, and scratched his chin, and moved from one part of the room to another, trying to get a good angle. He asked us to turn this way and that, which Killer took in good humor, but I could tell he was growing frustrated.

I said, “Just take the damn picture” to Friend B, but no, he was so finicky that he never snapped a single shot, just rehearsed for them, planned for them, considered them, rejecting chance after chance.

And that’s how I woke, repeating again and again, “Just take the damn picture! Take it! Take the damn picture!”

So that is what my subconscious is telling me I must REALLY think of these two friends. One is inept, and the other finicky.

And both shall remain nameless.

Where You’ll Find Me at World Fantasy Con 2010

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

Posted date:

October 19, 2010 |

No comment

Assuming I can pull my nose away from the grindstone, I’ll be in attending World Fantasy Con 36 in a week and a half. (My first WFC was the 5th, way back in 1979 in Providence.)

For those who’ll also be in Columbus, here’s where you’ll be able to find me (when I’m not off visiting all the restaurants Adam Richman hit on Man v. Food):

The Moral Distance Between the Author and the Work

Saturday, October 30, 4:00 p.m.

What do we make of good art by bad people, or at least people of whom we disapprove? Richard Wagner was a particularly vile anti-Semite, but he still wrote “Kill Da Wabbit!” and other great music. Should we listen? The official Nazi film industry made one very good fantasy film (BARON MUNCHAUSEN, to which the Terry Gilliam version owes a good deal). Should we watch this? What about an author who is a convicted child molester? Should we read his novel? CAN we read it for itself? Is it possible to truly experience any form of art as a thing until itself, rather than the product of its creator?

with Kathryn Cramer, Jack Skillingstead, Robert Sawyer, Paul Witcover

EC Comics and Their Influence

Sunday, October 31, 11:00 a.m.

A lot of baby boomers (not just Stephen King) grew up reading this stuff. How did this effect both their sensibilities and plotting skills?

with Andy Duncan and Gini Koch

And just so you know I’m not kidding about Man v. Food, check out the show’s Columbus episode: (more…)

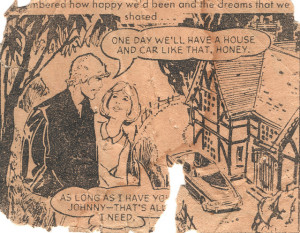

During a trip Irene and I made to London in 1977, the year after we’d gotten married, I found a panel in a British romance comic that seemed to represent our future. Hopeless romantic that I am, I cut it out and carried it in my wallet for several decades until it began to crumble, at which point I realized I’d better set it aside before it completely fell to pieces.

Here’s all that’s left of it.

I no longer have any memory of what comic this panel is from. But since you were all so helpful in solving my last comics mystery, it occurs to me that one of you must know. So—any ideas?

(Check out a larger scan of the panel over on Flickr if you think it would help.)

How Much Did Writers and Editors Earn in the 1800s?

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

Posted date:

October 17, 2010 |

No comment

If you’re bored by what publishing was like in 1850 and before, avert your eyes! But as for the rest of you …

The two previous excerpts I posted from the September 1850 issue of Harper’s dealt with the culture of publishing, and the writer/publisher relationship, but neither piece really delved into what writers and editors might be expected to earn at their trade back then.

Two different short articles in the issue give some idea. The first is about the history of The Edinburgh Review. Here’s what the contributors to and editors of the magazine earned:

Sidney Smith’s account of the origin of the Edinburgh Review is well known. The following statement was written by Lord Jeffrey, at the request of Robert Chambers, in November, 1846, and is now first made public: “I can not say exactly where the project of the Edinburgh Review was first talked of among the projectors. But the first serious consultations about it—and which led to our application to a publisher—were held in a small house, where I then lived, in Buccleugh-place (I forget the number). They were attended by S. Smith, F. Horner, Dr. Thomas Brown, Lord Murray, and some of them also by Lord Webb Seymour, Dr. John Thomson, and Thomas Thomson. The first three numbers were given to the publisher—he taking the risk and defraying the charges. There was then no individual editor, but as many of us as could be got to attend used to meet in a dingy room of Willson’s printing office, in Craig’s Close, where the proofs of our own articles were read over and remarked upon, and attempts made also to sit in judgment on the few manuscripts which were then offered by strangers. But we had seldom patience to go through with this; and it was soon found necessary to have a responsible editor, and the office was pressed upon me. About the same time Constable was told that he must allow ten guineas a sheet to the contributors, to which he at once assented; and not long after, the minimum was raised to sixteen guineas, at which it remained during my reign. Two-thirds of the articles were paid much higher—averaging, I should think, from twenty to twenty-five guineas a sheet on the whole number. I had, I might say, an unlimited discretion in this respect, and must do the publishers the justice to say that they never made the slightest objection. Indeed, as we all knew that they had (for a long time at least) a very great profit, they probably felt that they were at our mercy. Smith was by far the most timid of the confederacy, and believed that, unless our incognito was strictly maintained, we could not go on a day; and this was his object for making us hold our dark divans at Willson’s office, to which he insisted on our repairing singly, and by back approaches or different lanes! He also had so strong an impression of Brougham’s indiscretion and rashness, that he would not let him be a member of our association, though wished for by all the rest. He was admitted, however, after the third number, and did more work for us than any body. Brown took offense at some alterations Smith had made in a trifling article of his in the second number, and left us thus early; publishing at the same time in a magazine the fact of his secession—a step which we all deeply regretted, and thought scarcely justified by the provocation. Nothing of the kind occurred ever after.”

Constable soon remunerated the editor with a liberality corresponding to that with which contributors were treated. From 1803 to 1809 Jeffrey received 200 guineas for editing each number. For the ensuing three years, the account-books are missing; but from 1813 to 1826 he is credited £700 for editing each number.

But what do those numbers actually mean? (more…)

Writing for Magazines 160 Years Ago

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

Posted date:

October 16, 2010 |

No comment

My previous post shared an article from 160 years ago on what the world of book publishing was like back then. But what if you were around in 1850 and wanted to write for magazines instead? Luckily, the same issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine had some tips for that, too.

The one passage that stood out for me the most suggested that it was the job of reporters of the day to make politicians sound better than they were:

“The reporter is the speaker’s editor, and a very efficient one too. In a large number of cases, the speaker owes more to the reporter than he would willingly acknowledge. The speech as spoken would often be unreadable, but that the reporter finishes the unfinished sentences, and supplies meanings which are rather suggested than expressed.”

I know that journalists still do some of that today, but I’m glad that tradition has for the most part faded away. It shouldn’t be the job of a reporter to collude with politicians to make them sound smarter than they actually are.

Here’s the full text:

(Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 1, No. 4, September, 1850)

Lord Lyndhurst once said, at a public dinner, with reference to the numberless marvels of the press, that it might seem a very easy thing to write a leading article, but that he would recommend any one with strong convictions on that point, only to try. We confidently appeal to the experience of all the conductors of the leading journals of Great Britain, from the quarterly reviews to the daily journals, convinced that they will all tell the same unvarying tale of the utter incompetency of thousands of very clever people to write articles, review books, &c. They will all have the same experiences to relate of the marvelous failures of men of genius and learning—the crude cumbrous state in which they have sent their so-called articles for publication—the labor it has taken to mould their fine thoughts and valuable erudition into comely shape—the utter impossibility of doing it at all. As Mr. Carlyle has written of the needle-women of England, it is the saddest thing of all, that there should be sempstresses few or none, but “botchers” in such abundance, capable only of “a distracted puckering and botching—not sewing—only a fallacious hope of it—a fond imagination of the mind;” so of literary labor is it the saddest thing of all, that there should be so many botchers in the world, and so few skilled article-writers—so little article-writing, and so much “distracted puckering and botching.” There may be nothing in this article-writing, when once we know how to do it, as there is nothing in balancing a ladder on one’s chin, or jumping through a hoop, or swallowing a sword. All we say is, if people think it easy, let them try, and abide by the result. The amateur articles of very clever people are generally what an amateur effort at coat-making would be. It may seem a very easy thing to make a coat; but very expert craftsmen—craftsmen that can produce more difficult and elaborate pieces of workmanship, fail utterly when they come to a coat. The only reason why they can not make a coat is, that they are not tailors. Now there are many very able and learned men, who can compass greater efforts of human intellect than the production of a newspaper article, but who can not write a newspaper at all, because they we not newspaper-writers, or criticise a book with decent effect, because they are not critics. Article-writing comes “by art not chance.” The efforts of chance writers, if they be men of genius and learning, are things to break one’s heart over. (more…)

What Was the Publishing World Like in 1850?

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

Posted date:

October 16, 2010 |

No comment

I downloaded a 160-year-old magazine last night and discovered a fascinating essay about the way the publishing world worked back then, which turned out to be not at all alien. Writers were complaining that publishers weren’t paying them enough, publishers were explaining that they needed bestsellers to offset the losses of less profitable books, and good books often went unpublished when they just didn’t seem commercial enough.

I love old magazines—especially those not just of last century, but the one before that—and find it especially delightful to be reading a magazine from 1850 on my iPad. (Thank you, Project Gutenberg!) I don’t even miss that musty smell of old paper—and especially not the loss of those crumbly bits that usually end up all over my desk.

I hope you can make your way through the massive paragraphs that were the style of another generation so you can read the lengthy description of writers near the end, for after all, “Literary men are sad spendthrifts, not only of their money, but of themselves. At an age when other men are in the possession of vigorous faculties of mind and strength of body, they are often used-up, enfeebled, and only capable of effort under the influence of strong stimulants.”

Sound like anyone you know?

(Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 1, No. 4, September, 1850)

It is a common complaint that the publishers make large fortunes and leave the authors to starve—that they are, in fact, a kind of moral vampire, sucking the best blood of genius, and destroying others to support themselves. A great deal of very unhealthy, one-sided cant has been written upon this subject. Doubtless, there is much to be said on both sides. That publishers look at a manuscript very much as a corn-dealer looks at sample of wheat, with an eye to its selling qualities, is not to be denied. If books are not written only to be sold, they are printed only to be sold. Publishers must pay their printers and their paper-merchants; and they can not compel the public to purchase their printed paper. When benevolent printers shall be found eager to print gratuitously works of unsalable genius, and benevolent paper-merchants to supply paper for the same, publishers may afford to think less of a manuscript as an article of sale—may reject with less freedom unlikely manuscripts, and haggle less savagely about the price of likely ones. An obvious common-place this, and said a thousand times before, but not yet recognized by the world of writers at large. Publishing is a trade, and, like all other trades, undertaken with the one object of making money by it. The profits are not ordinarily large; they are, indeed, very uncertain—so uncertain that a large proportion of those who embark in the publishing business some time or other find their way into the Gazette. When a publishing firm is ruined by printing unsalable books, authors seldom or never have any sympathy with a member of it. They have, on the other hand, an idea that he is justly punished for his offenses; and so perhaps he is, but not in the sense understood by the majority of those who contemplate his downfall as a retributive dispensation. The fact is, that reckless publishing is more injurious to the literary profession than any thing in the world beside. The cautious publisher is the author’s best friend. If a house publish at their own risk a number of works which they can not sell, they must either go into the Gazette at last, or make large sums of money by works which they can sell. When a publisher loses money by a work, an injury is inflicted upon the literary profession. The more money he can make by publishing, the more he can afford to pay for authorship. It is often said that the authors of successful works are inadequately rewarded in proportion to their success; that publishers make their thousands, while authors only make their hundreds. But it is forgotten that the profits of the one successful work are often only a set-off to the losses incurred by the publication of half a dozen unsuccessful ones. If a publisher purchase a manuscript for £500, and the work prove to be a “palpable hit” worth £5000, it may seem hard that the publisher does not share his gains more equitably with the author. With regard to this it is to be said, in the first place, that he very frequently does. There is hardly a publisher in London, however “grasping” he may be, who has not, time after time, paid to authors sums of money not “in the bond.” But if the fact were not as we have stated it, we can hardly admit that publishers are under any kind of obligation to exceed the strict terms of their contracts. If a publisher gives £500 for a copyright, expecting to sweep the same amount into his own coffers, but instead of making that sum, loses it by the speculation, he does not ask the author to refund—nor does the author offer to do it. The money is in all probability spent long before the result of the venture is ascertained; and the author would be greatly surprised and greatly indignant, if it were hinted to him, even in the most delicate way, that the publisher having lost money by his book, would be obliged to him if he would make good a portion of the deficit by sending a check upon his bankers. (more…)