Follow Scott

Recent Tweets

- Waiting for Twitter... Once Twitter is ready they will display my Tweets again.

Latest Photos

Search

Tags

anniversary Balticon birthdays Bryan Voltaggio Capclave comics Cons context-free comic book panel conventions DC Comics dreams Eating the Fantastic food garden horror Irene Vartanoff Len Wein Man v. Food Marie Severin Marvel Comics My Father my writing Nebula Awards Next restaurant obituaries old magazines Paris Review Readercon rejection slips San Diego Comic-Con Scarecrow science fiction Science Fiction Age Sharon Moody Stan Lee Stoker Awards StokerCon Superman ukulele Video Why Not Say What Happened Worldcon World Fantasy Convention World Horror Convention zombies

©2025 Scott Edelman

Rescuing my long-ago lunch with Samuel R. Delany

Posted by: Scott

Tags:

Samuel R. Delany, Science Fiction Weekly, Syfy

Posted date:

January 25, 2015 |

No comment

I’ve been thinking quite a bit about Chip Delany and his writing recently, as evidenced by this post from a few weeks back, and that resulted in me suddenly remembering an interview I conducted with him more than thirteen years ago in support of the release of his 1974 novel Dhalgren.

The nearly 6,000-word interview originally ran on June 18, 2001 in Science Fiction Weekly #217. The contents of that magazine vanished from anywhere online save the Wayback Machine when Science Fiction Weekly merged with SCI FI Wire—or maybe it was when SCI Wire transformed into Blastr—taking this interview with it, which seems a shame. So here it is once more, rescued from the black hole of the Internet, following my original introduction …

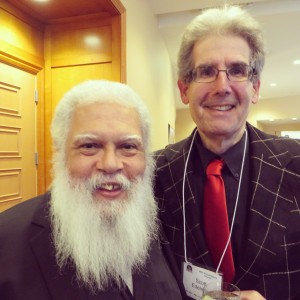

(This photo of us, however, is from May 2014.)

Samuel R. Delany launched his science-fiction career as a 20-year-old publishing prodigy with the novel The Jewels of Aptor in 1962. Other critically-acclaimed novels and short stories quickly followed, as did recognition from both fans and peers. He earned Nebula Awards for his novel Babel-17 (1966), as well as the short stories “Aye, and Gomorrah … ” (1967) and “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” (1969), the latter of which also won a Hugo Award. By 1969, the author, editor and critic Algis Budrys was already calling Delany “the best science-fiction writer in the world,” which, based on the evidence at the time, did not seem to be that controversial a call.

The true controversy waited just around the corner. For at the height of his success, Delany sequestered himself to spend half a decade on his next project, Dhalgren, which when eventually published in 1974 was like no science-fiction novel seen before. The 800-page novel used experimental literary techniques to tell an apocalyptic tale containing explicit explorations of sexuality, race and gender. The controversial novel was either loved or hated, proving to be the most hotly debated SF novel of the decade. Vintage Books has just begun a publishing program to reissue all of Delany’s classic novels, beginning with Dhalgren.

Science Fiction Weekly interviewed Delany over lunch at the Hotel George in Washington, D.C., while he toured the country to promote Dhalgren‘s new home.

Let’s go back in time to the science-fiction field before Dhalgren. I was just reading an essay by Bob Silverberg in the April 2001 issue of Asimov’s. In his latest column, he tried to make sense of the New Wave, and the first writer he mentioned in trying to explain the American wing of the New Wave, the first name that came up, was yours. Why do you think that is?

Delany: I have no idea.

Do you agree with that assessment?

Delany: The problem is, it depends what you mean by the New Wave. I think if you mean the real New Wave, no, I had nothing to do with it. Which is to say, by that I mean, the writers who clustered about Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds in England. But there are different waves. The New Wave has several waves. If you start talking about an American wave of the New Wave, you can put anyone in it. And I certainly don’t mind being put in it.

What was the feeling in the field prior to coming up with Dhalgren, which was a new thing in and of itself? Try to explain for us a little bit about the environment of the field at the time.

Delany: Of course, I was so busy writing Dhalgren I had no idea what the field at the time was doing. It was five years when I really was kind of out of contact with the field per se. Before Dhalgren—and I don’t really know whether you can start to talk about science fiction before and after Dhalgren, that seems a rather arbitrary cutting-off point—but books tended to be shorter. There were more shorter books. Paperback novels tended to be around 60-70,000 words. There was a feeling that big books did particularly well, but everybody wasn’t encouraged to write them.

Now you can go down the science-fiction shelves and there’s nothing under 350 pages. That’s one of the differences I should think in the field now; everyone is encouraged to write really long books. There was a lot less fantasy. There was a lot more hard science fiction, and fantasy was really a small subset of the genre, although Tolkien had come out and made a big splash towards the end of the ’60s. Nevertheless, the notion that everybody could write a seven-volume trilogy of fantasy novels hadn’t taken over yet.

And the field was a little smaller. People knew each other a little better. Those are the main differences. The field was a little smaller, thus making it more knowable.

When you talk of books being 60,000 words long, I remember that you’ve written about your first editor, Donald Wolheim, and saying that he reacted to your first book by saying it was a work of genius and a masterpiece, but that you had to cut it down to 160 pages.

Delany: 146. In fact, he put it, “you need to lose 750 lines. So just find 750 lines and cut, because it’s got to fit in 146 pages.” The long side of an Ace Double.

So coming into an environment like that, what made you decide to sit down and turn to a book like Dhalgren?

Delany: Sheer madness. When I wrote Dhlagren, I wanted to write a big book. I wanted to write something that was major. It was a book written entirely for me. I really didn’t have any idea. I was quite prepared for the book not to even sell. It had to go through a couple of publishing companies before it did. And when it did, I think after four or five, I was really quite surprised. One of the things that happened to it—it got accepted at Doubleday on Friday, and then the following Tuesday it was rejected again. And the editor who accepted it was very embarrassed, as you might imagine.

So was this the first book where you switched over from being the sort of science-fiction writer who had a contract based on a proposal, and instead finished the entire book first and sold it from there?

Delany: No, my first few books I didn’t have a contract for. The first five books I didn’t have a contract for, although at that time I was working for Ace. Indeed, Dhalgren was the book that I learned that doing contracts first is not what I want to do. Dhalgren started out, the original prospectus for the book, was for a series of five political novels that was with Avon Books, who drew up a contract for them. The idea was that things that I had seen burgeoning in the counterculture at that particular time were going to result in the overthrow of five different types of government: A kind of a more extreme industrial consumer capitalism than we actually have in America; a more oppressive collectivist government; a classical dictatorship; an ordinary parliamentary government; and then a government where everything runs by bribes. And in each book these governments were going to be overthrown by a group of people just exercising the wonderful world view of the flower children.

And when did that change in the writing process?

Delany: It changed after I’d been working on it for about six months. And I moved from New York to San Francisco over the New Year’s/Christmas holidays of 1968/1969. By the time I got to San Francisco, somewhere on the plane, I guess, I realized that I wanted to do something a lot more unified. I wanted to write one big book. And I also wanted to do something that was less intellectually executive. My initial vision of the whole thing was kind of Alfred Bester far-future novels with lots of repartee by George Bernard Shaw. And I decided I wanted to do something more poetic and write one novel. So when I got to San Francisco, I set about doing it.

Five years later, there was the novel.

When the book was actually published, the first thing that the casual reader would see was, as I recall, a quote on the cover that I think Fred Pohl might have written, that said “In the tradition of Stranger in a Strange Land,” or something like that. What was he getting at?

Delany: I have no idea. What you simply did at that point, what you did with any science-fiction novel, was pick the largest selling science-fiction novels, and every science-fiction novel because it was science fiction was in the tradition of the largest-selling science-fiction novel. That’s all that was going on there, I think.

Looking back on it now from this expanse, has it gotten to be something more than that? It now joins the list as one of those books that are still around, still on people’s minds after many years.

Delany: Well, now I suppose a few people will say “in the tradition of Dhalgren.” I don’t know.

In the afterword to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig wrote of the Swedish concept of “kulturbarer,” which translates as a culture-bearing book. He wrote that “a culture-bearing book, like a mule, bears the culture on its back. … Culture-bearing books challenge cultural value assumptions and often do so at a time when the culture is changing in favor of their challenge.” And he also writes that “No one should sit down to write one deliberately.” And yet, you have. You did.

Delany: Well, I followed his advice, I didn’t do it deliberately. If it’s done anything like that, I think that—in no way to denigrate what you’re saying—but that’s got to be in the eyes of the readers. And just for the same reason, the writer can’t say too terribly much about the whole process. I just wrote about what I saw around me and tried to turn it into something that I would recognize as a novel.

But in doing so, I assume that you had to anticipate the response of the field, that the response of readers would differ from the response given to your previous work and given to the other standard works at the time.

Delany: As I said, I was just hoping it would find a publisher. And when it did I was quite surprised. And when it did well I was even more surprised.

But when the response came, was it just “oh, great, here’s another Delany novel”? Was it the standard response? It treated sexuality in a different way. It treated culture in a different way. The field, and not just the country, was in a period of change.

Delany: The country was in a period of change. The book was fairly controversial. Some people liked it very much. Some people really hated it a whole lot. I was a little surprised by both responses. There was a lot of “This book is so bad I couldn’t read more than 50 pages of it.” And so a lot of the people who dismissed it dismissed it essentially without reading it. And then spent a lot of time saying, “And nobody else I know has been able to read more than 50 pages either.” But then again, it also went into multiple printings. It sold an awful lot of copies. And at a certain point, people looked around and noticed that the people with the higher I.Q.s were enjoying it a lot. And the people with the lower I.Q.s weren’t. So what could you say? And yet at the same time it seemed to pull the more intelligent readers out of the woodwork. Which is warming, for a writer.

With the number of copies sold, it obviously reached beyond the science-fiction genre audience.

Delany: One of the things that was very clear is that many of the readers were just general college-age readers, some of whom had read some science fiction, some of whom had not read a lot, but were responding to it. Again, I was very pleased by it. Most of the mail that it received, and it received a fair amount, didn’t talk about the style, didn’t talk about the density of the book or anything that seemed particularly literary. It was just “You’re writing about people I know, and I haven’t seen written about before.” Often accompanied by a thank you. That’s what seemed to initially attract people to it, is the kinds of people who were being written about in the book, who tend to be basically people who don’t work. I think a lot of people found this a little upsetting, kind of a whole cast of people who are basically drifters, who were hangers-on and moved into this landscape and don’t have jobs.

The book tells the story of a character who doesn’t quite know who he is, without memories, moving through an urban landscape during a period of chaos when things may or may not be happening that he’s trying to perceive about himself and the landscape around him. I keep coming back to science-fiction readers reading the book versus non-science-fiction readers reading a book. And you’ve spoken about that quite a bit. How is it perceived by those two split audiences—the science-fiction people accepting it as science fiction and the non-science-fiction people accepting it as a novel.

Delany: Well, I don’t know. You hope that the internal signs will be strong enough to hold readers to the text you’re writing. I would have thought that people who had read a fair amount of science fiction would have an easier time with the book than people who hadn’t read any science fiction at all. And indeed this is what I assume, most of the people who read it—somebody just called in to the interview that I just came from to say that he read the book six or seven times. And there are people who will go back to it and read it again and again. And these people frequently tend to be science-fiction readers. It’s not the non-science-fiction readers who come back again and again to read it.

One of the things you’ve talked about is the attention to the detail of the prose that separates a science-fiction story from a non-science-fiction story. A non-genre reader could read Dhalgren and not pick up on some of the clues that are buried in there. The science-fictional elements come out in a subtle way. I wonder if a non-genre reader might wonder, is that madness, or hallucination, where the genre reader might see different things to it.

Delany: I guess so. Talking about your own book is a very difficult thing to do, because as the writer, you never see the book from the outside. You’re always like somebody standing on the inside of a balloon with little pieces of adhesive tape trying to hold the thing to shape, but from inside. And then everybody else sees it from outside and they say, “Yes, that’s an interesting shape you’ve made,” but you never see that shape, because you’re within it. And so it’s a little hard for me to talk about what other people’s responses were. I was just busy standing in there and trying to hold the thing to keep it from going “pop” and blowing up again.

Dhalgren is just one of many books and essays you’ve written over the years on the importance of cities, or the importance of cities to you.

Delany: Yes, it’s very much a city novel. It was one of the things that does go into Dhalgren. At the end of the ’50s, in New York City, there was the beginning of a kind of exodus from Harlem and the South Bronx that by the middle of the ’60s left Harlem and the South Bronx deserted, burned-out, inner-city shells, just ruins and wrecks. And if this had just been a New York City problem, perhaps Dhalgren would not have been anywhere near as popular. But by the middle of the ’70s, and in the ’70s, ever major city in the country had its burned-out inner city, areas of the city that should have been prime real estate that frequently had been before black or Hispanic ghettos that now were just ruins—acres and acres, blocks and blocks of ruined city.

And these were the basic images that I used to create Dhalgren from. The city in the middle of the United States where something has happened, we don’t know what it is. We get hints that it might have been this, it might have been that, it might have been something else. But fundamentally it remains a mystery. But I think to most city dwellers of the late ’60s, early ’70s, these burned-out areas seemed like a kind of a malevolent black magic. There may have been socioeconomic explanations, and some people may have even had a handle on what those socioeconomic explanations were, but to just somebody walking around in the place, it looked like magic. So Dhalgren is an attempt to deal with the affect of those images rather than an attempt to explain them away in a logical way. It’s rather an attempt to sort of deal with what those parts of the city felt like.

Has your approach to the urban landscape changed in the past few decades? If you were writing a similar novel today, what story would it tell of the city today?

Delany: I don’t know what it would tell, really. I think it would want to … I am writing a novel about the city, actually, and the story is a very different one. But the basic enterprise is to tell what the city feels like, rather than to explain the whole thing away with facts and figures. That’s what you do in nonfiction, which I write, too. I wrote nonfiction about the city as well. Basically what I like to do in novels is image first, explanation later.

One of the things I was wondering as I was reading Dhalgren is that I know that all writing is autobiography, but I wonder if you had as much pain writing as the Kidd, your protagonist, did. This is someone for whom the act of creation is horribly painful. What exactly was that aspect touching in you at the time, if anything?

Delany: I think there are lots of similarities between the Kidd and me. He has the same response to typographical errors that I do. Which is to say, I find them really painful. I think I’ve learned to deal with them a little bit better than he has. I don’t fall on the floor and start to have seizures. The Kidd is essentially dyslexic, and so am I. And a lot of the things that he goes through are sort of dyslexia writ large.

Regarding your sensitivities to typographical errors, I read your correspondence in 1984 and essays elsewhere about dealing with them in subsequent editions of Dhalgren over the years. It seems as difficult to get the perfect Dhalgren as to get the perfect Ulysses.

Delany: Just about. I’ve already started to make a list of typographical errors for the Vintage edition, of which I think I’ve got seven or eight at this point. So on page 75, vocabulary has got an extra “l” in it, and things like that.

So how many different states do we have over the years?

Delany: Not that many. Again, you have to remember that they’re just spelling mistakes basically. It’s just a matter of trying to get the text as close to its own ideal form as you can.

John Crowley was being interviewed recently in Locus and he gave a list of those who came before him and what he had to thank each for. He thanked J.G. Ballard for teaching him “restraint and melancholy.” He thanked Ursula K. Le Guin for teaching him “the possibility of feeling.” You he thanked “for extravagance.” What do you think he meant by that?

Delany: It sounds like a compliment to me, and you don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. I will simply accept it graciously and go on about my business. I don’t know. I’m not sure what he means by extravagance, although it feels right to me. I’m kind of an extravagant guy.

You’re spending a lot of time teaching these days, dedicating a lot of your time to that—

Delany: More time teaching than writing.

I know what the kids must be getting out of it, but what is your reward here?

Delany: Well, I like teaching. Watching ignorance self-destruct is a joy. And when I can see ignorance being displaced by some kind of knowledge and to suspect that I had a slight hand in it, showing them how to nudge some of the incorrect notions out of the places they’ve gotten mired in so better notions can come in and sit there, that’s always a very rewarding thing to be involved in.

These are history of the genre and comparative literature and creative writing courses?

Delany: Literature courses and creative writing courses. I haven’t been teaching much science fiction recently. Although, next term I’m going to be teaching an introduction-to-science-fiction course for the first time in about five years.

You yourself were not a product of the creative writing academic world.

Delany: Not the university creative-writing background. One of the most influential courses I ever took was a high school creative writing course, which I think if I hadn’t taken it, I don’t think I probably would be a writer. What was most important was not anything I particularly learned about writing, but basically being around a lot of other people who also were very, very devoted to writing. Very, very committed to being writers. Like Marilyn Hacker, whom I eventually married. And a number of other people as well. Some of them went on to be professional writers. A guy named Stuart Byron who became a journalist. A guy named Mike Goodwin, who also became a journalist. A man named Sheldon Novak, who only a couple of years ago published a very controversial biography of Henry James. Norman Spinrad was a year ahead of me in high school, although I didn’t know him at the time. I didn’t meet him until a decade later.

In dealing with the students, have you ever seen the light bulb go off? What do you see when you see that happen, see someone get it? Someone didn’t have it, and then all of a sudden something clicks.

Delany: It’s not a light bulb that goes off. Actually, they suddenly breathe more easily, and the whole world looks more logical to them. That’s a very good thing to see. Because that’s why I think people do study, that’s why people do learn. Because suddenly their world looks more coherent to them. It’s not a matter of learning a particular fact. Just to learn the way the world works in general, which I think is the major purpose of education.

A puzzle piece suddenly slides into place in their minds, and they see things differently?

Delany: Though usually it’s about 27 puzzle pieces all turn one-quarter of an inch, and suddenly all fit in place. And the whole thing that looked like confusion before suddenly seems like order.

And can that be replicated?

Delany: You can certainly help people to have that experience. And teachers can certainly help students to have that experience. And I think that’s a good thing when it happens.

Have you perceived any change in the educational system as you’ve been teaching in it all these years? Have you seen a difference in the students as they come to you?

Delany: Yes. I think students have a lot less of what people from my generation would think of as basic intellectual background. On the other hand, they have immense knowledge of things like television and popular music and sometimes movies and just cultural change that I’m not privy to all all. Goethe says somewhere that a man of 50 knows no more than a man of 20, they just know different things. And I think that’s fundamentally true. But nevertheless, every once in a while it’s surprising to me some of the things that they don’t know.

I remember during the early days when I was teaching up at U. Mass, at one point I had a class of about 32 people, and I was talking about the changes in art that happened at the beginning of the 20th century. I said “Picasso, Cezanne,” and I noticed there was a kind of blank look. And I said to them, “How many of you have ever heard of Cezanne?” Two people put their hands up in a class of 32. “How many people have ever heard of Picasso?” Less then 10 people in the class knew the name Picasso.

A couple of years later, we had a little coffee shop open up in Northampton right outside of Amherst, called Naked Brunch. And on every bus stop around the city, there was a little poster for Naked Brunch. And I was trying to explain to them the theoretical notion put forth by a man named Michael Riffaterre of a hypogram, that is to say, the notion of a sentence or a phrase that underlies a modern sentence that makes that sentence funny. So I said, “One example of this would be Naked Brunch. You’ve all seen the posters and you all know the name of the novel that they are playing with.” “Novel, novel, what novel?” They didn’t know. They didn’t know that that was a play on Naked Lunch at all. And so I had to back off.

And every once in a while one of the things that happens to the teachers is that he realizes that he’s not talking to the same people he thought he was talking to. Or she was talking to, as the case may be. And that’s one of the things that happens more and more. I realize that the kids don’t have that background information that frequently just makes the world make sense. Like knowing what the name of a restaurant is based on.

As an author, how do you deal with that? I was just rereading Dhalgren, with almost 30 years between readings, and I don’t perceive the kind of blatant allusions to the current popular culture that would make it unrecognizable to someone now, the way someone reading Stephen King in 30 years might say, “I don’t recognize these brand names.” Dhalgren seems to be something that doesn’t appear dated in the way that certain other literary things do.

Delany: This is why I just follow the rules of Strunk and White. Don’t clutter up your things with local references, because in two to five to 10 years, no one is going to recognize them any more. It’s one of the things that makes Stephen King very popular, but at the same time he may be the kind of writer who needs academics to make the work make sense in 15 to 20 years, because of all the brand names. I mean, they become the equivalent of the literary references in Ulysses. Only people who are experts in 1980s’ consumer culture will be able to negotiate those novels.

There are other allusions, such as when your protagonist goes down the list of his possible names, and the reader sees that, oh, the name Disch is in there. Within the novel it doesn’t have meaning. It has an extra-artistic meaning. But the science-fiction reader at the time would read that and make a connection.

Delany: It isn’t that meaningful in the book. I mean, basically, I had just met Tom Disch’s younger brother, and I was looking for names and I thought, well, let me use him. Probably if I were doing it today I probably wouldn’t, simply because it does bring too much baggage to it. It’s supposed to be a neutral name. And I used it because I just met Gary, his brother, and I put Gary Disch down there. But knowing that Disch is the name of a science-fiction writer, it doesn’t open up any part of the novel for you in any particularly interesting way.

It’s like Ashton Clark in Nova. Science-fiction readers see that and the first thing they think of is Clark Ashton Smith. When I wrote that, I was naive. This was just a point where I didn’t know fandom very well. I thought Clark Ashton Smith was somebody that I had discovered and nobody else would know. And yes, I had Clark Ashton Smith in mind when I made up the name, but I was using it under the assumption that nobody would bring any associations to it at all. And then for the next 10 years I had people, say “Why did you name the scientist after Clark Ashton Smith?” To which the answer is, I don’t know. I didn’t think anyone would notice. And of course, everybody noticed. And I also assumed that if someone did notice, they’d think it was a little in-joke and go on, and wouldn’t stop and dwell on, because I certainly didn’t.

Tell me a little more about Dhalgren. I know you said it’s hard to talk about from the inside.

Delany: And especially after 25 years. There are writers who really hate all their old work. And writers who love all their own work, I suppose. I’m kind of somewhere in the middle. By no means do I hate it. I still can get pleasure out of rereading certain passages. But at the same time, I don’t spend a lot of time dwelling on it. It’s 25, 26, 27 years in the past, and I’m doing other things.

Tell me about some of those things. You say you’re working on a new novel?

Delany: I’m finishing up another novel. I tend not to talk about the novels I’m working on now, because if I talk about them I don’t write them. I’m working on some nonfiction projects. I’m working on an essay about Harlem in my youth, my reminiscences of Harlem. And also what it means in the sort of calculus of images in America, and what it meant at particular times. That’s one of the things I’m putting in a fair amount of energy in. And then I’m writing all sorts of written interviews having to do with Dhalgren, because this is the week it’s coming out from Vintage, and they’ve been setting up all these interviews and what have you, and I’m trying to rise to the occasion in a gentlemanly fashion.

It seems that writing about Harlem is once more writing about an urban setting, such as Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. Can you imagine yourself living in the countryside, on a farm, outside of an urban setting? Does Chip Delany exist then?

Delany: Absolutely not. No, I’m a city boy. And I’m a city lover. I really like cities. The word “civilized” of course means city. Civilization is something that happens in the cities. I don’t think it really happens in the country, other than by people trying to imitate what they see happening in cities.

I got out of New York when I turned 30, and I never considered moving back to the city until I read an interview with you in Publisher’s Weekly. I always thought, I have the telephone, the Internet, I’m in contact with all of my peers, and so on. But you were talking about the happy accidents that can occur in the city, which is something that I hadn’t thought of before, and that made me start to reconsider.

Delany: I think that’s one of the things that makes city life really fascinating. By and large, what just meeting people by accident does is it just stabilizies a general level of pleasantry, which I think is very important, too. But every once in a while those accidental meetings, there’ll be some transfer of material goods. In a book called Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, I talk about some of these things. One day, my vacuum cleaner gave out, so I took it down and left it on the street and then walked up to the local copy center. And while I was standing in the copy center getting some copies made, this guy comes in and says, “I got a dry-wet vacuum cleaner here—10 dollars. Anybody? Who wants it?” At first I thought he’d gotten my vacuum cleaner. But it wasn’t. It was a new vacuum cleaner. It was from some construction site, and the people who had brought it there didn’t want it, he didn’t want to take it home, and so he just wanted to sell the thing for ten bucks. So I walked home with a new vacuum cleaner, rather than having to go and spend $100 on a new vacuum cleaner.

The prostitute who picks up a client who just happens to have some money so ends up spending a weekend in the Hilton and has a great time. And in the course of it decides, well, maybe, “I want to lead a better life than I’d been leading before,” and decides to change her way of living. This kind of thing happens all the time in cities. We live in a society that claims to value the movement from class to class, that you can make your way up through the various social levels. Well, if the various classes don’t have contact with one another, if they’re not close to one another, then how are you going to make your way up through the classes, if there is no actual contact between the classes? The best you can do is run around on the same level, if you don’t have the contact between the classes.

Where are the cities going? Are they stratifying? I know you probably didn’t use the word Disneyfication, but other people have. Where are we going?

Delany: Good question. I do think people are trusting contact relationships less and less. And that’s because big business tends to demonize them. “Oh, terrible things will happen if you meet people of different classes. They’ll rip you off! You’ll lose things! It’s unsafe! You’ll get AIDS!” Everything from one to the other. And there’s a lot of this demonizing of interclass contact, which I think is the demonizing of city life itself. But city living, living with strangers, living with lots of different kinds of people and learning to live with them, is a very exciting thing. I’ve alway found living in the city to be a very exciting experience, because you do have contact with so many different kinds of people.

And you’re now in Philadelphia. Is that a whole new city to learn?

Delany: It’s a very different kind of city with a very different feel. One I like a lot. I commute back and forth from New York to Philadelphia. And it’s very interesting, because the feeling in Philadelphia is so different from the feeling in New York.

How do they differ?

Delany: Philadelphia feels to me, it strikes me, as the way New York used to feel in the late ’40s, early ’50s. It’s a lot more laid back. Its a little friendlier. And it’s vigorous without being hard-assed, which I like. Which I’m quite fond of.

With all the going back and revising on Dhalgren, you obviously perceive something special and different about it from your other books.

Delany: No. I think I work as hard as I can on everything I write. Anything that I don’t think I’ve written absolutely as hard and put in as much work as I possibly can I probably wouldn’t publish.

But you’ve been continually correcting typos, as can be seen by your essays on it and published correspondence in 1984 and elsewhere. Getting a more perfect Dhalgren has been more difficult than getting a more perfect Babel-17.

Delany: Often that’s just different publishers. Dhalgren is so large that it’s more difficult. Some books come out with remarkably fewer typographical errors than others. Dhalgren had more than its share from the very, very beginning. I was never sent the copyedited manuscript to read. Dhalgren, when it was a manuscript, it went off, and the next thing I got were galleys, so I never had the copyedited manuscript. And I only had the galleys for four days. You try to correct 800 pages of galleys in four days; it’s an undoable task. And given that that’s how it was done, I think Bantam did a remarkably good job. But there were hundreds of errors in the initial publication. And slowly but surely they got it down to a reasonable number of errors. And when Wesleyan redid the book, again, it was done a little too fast, it was rushed and nobody proofread it, with the result that suddenly there were another hundred-odd errors that crept in. And Vintage is very nice. Most of the errors of correction at this point are done not by me, but by other people who call up and say, “Hey, on page 373, there’s no period at the end of this sentence.” And I look, and sure enough, they’ve left out a period.

Do you ever wake up from a nightmare of one of your early editors telling you that you had to cut Dhalgren down to 146 pages?

Delany: No. [Laughs.] What a thought! I probably will tonight for the first time.